Night Shift At Camden Fringe

The great attraction of Fringe Festivals is the unbridled hope that one left turn may lead to something extraordinary. The thrill of being in on some secret - of being early to a show or to an artist whose audience you confidently expect to grow in the future - keeps us, or at least keeps me, wandering wide-eyed down alleyways each August.

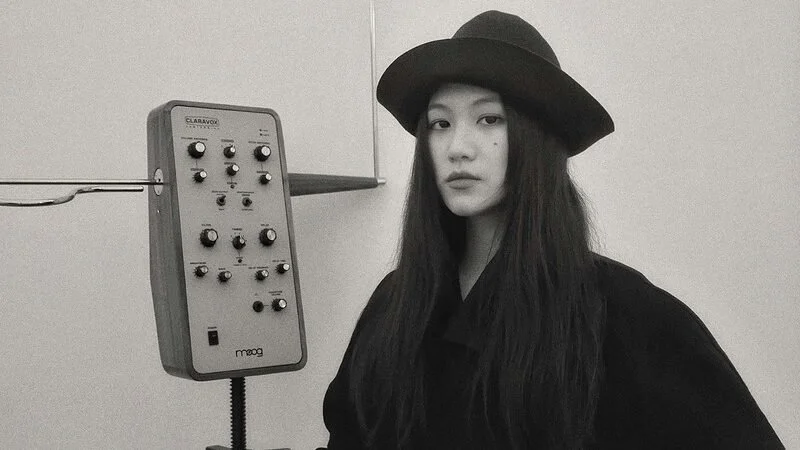

This annual hunt for private magic came to its happy conclusion in a small theatre above The Lion and Unicorn Pub at this year’s Camden Fringe, where at about a half-past eight last Friday night I shuffled my feet and awaited the arrival on stage of Ellen Turner.

Turner’s new comedy, Night Shift, is set essentially over a few minutes as she waits for a bus home following a night out. Turner - who stars in the show - regales us with a crude and witty monologue. The Fleabag comparisons will be inevitable - even to those of you who haven’t seen the show - so let me address them here. What distinguishes Turner’s work from Bridge’s is simple to say and hard to come by: earnestness. The pervading irony beneath Bridge’s observations in Fleabag - the wry smile, the knowing wink - are in fact class signifiers of the artist behind them.

Night Shift’s sensibilities are something else entirely, perhaps owing to its working class dramaturg Maisie Newman. The play’s context is not a smug and twee complacency; our heroine feels defiant, assured, but never quite safe. As a working class viewer, I found this undercurrent of dislocation and instability profound.

Forthrightness is not the only characteristic of Night Shift that separates it from - and in my view elevates it above - productions with similar ideas. Whilst waiting at the bus stop, Turner is winked at by a man she doesn’t know. What follows - and what comprises the body of the show - is a hallucinatory descent through the layers of patriarchal tyranny within modern society.

It’s at this moment - with clever directorial tricks I won’t ruin for you - that the show enters its strange glory. Those tricks are the work of Director Maisie Newman, who also worked as a dramaturg and sound designer on the production. Newman’s is a brain whose outputs I’ve been treated to before - and there’s a non-zero chance I’d have identified Night Shift amongst her portfolio around ten minutes in.

Newman has a knack for stretching scripts to the edge of their world, for interrogating ideas and ripping away like Russian Dolls all euphemism and cowardice, leaving only the basal truth, stark on stage, naked and beautiful.

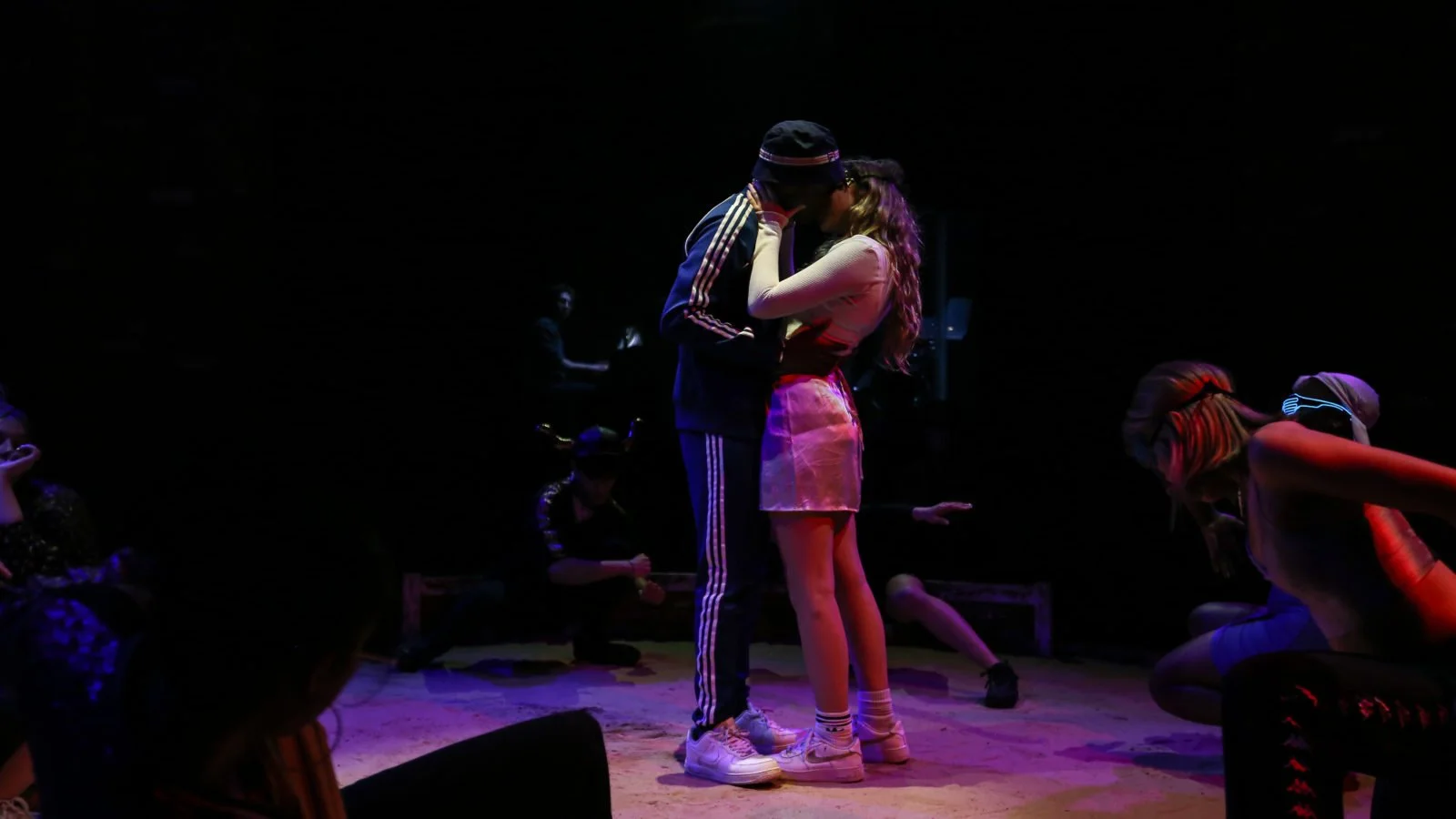

The winking man, played by Alex Gannon, metamorphoses into various iterations of patriarchal archetypes. Gannon’s performance in a challenging role is legitimately sublime. He hits the comic beats expertly, and is by turns unnerving and patronising as he transfigures from therapist to talk-show host. It is Gannon, really, that manages our descent toward archetypical truth and origin, and he does so fantastically.

The stylishness and pace of the show is thanks in part to the composition of Jack D’Arcy. This attribute is especially welcome during Gannon’s early scenes - where the sound design does a great deal of work both tonally and in landing jokes dependent on sharp timing.

Carys Lester as Stage Manager was assisted by Jay Pykett, who doubled on lighting, providing the show with its purple hues. Gayané Kaligian produced the show.

Night Shift is fundamentally the vision of Ellen Turner. Turner’s performance is exemplary, she is a wonderful actor. Most striking, though, is her pen. Turner is a truly, truly gifted writer. Night Shift fizzes with darkly comic energy, talks in plain-english of cum and wanks and rape, but what soars in this production - alongside its directorial surrealism - is its poetic quality. For all of her talent in sharp brutality, when Turner’s gaze turns gentle she writes with an ache that sings.

Great shows cling to you, and it was Turner’s effervescent imagery that busied my mind as I strolled through Camden, stared at smoke, wondered aloud how it feels to drown, missed the bus, made it home.

Image credit: Gianmarco La Ruffa

Theatre Criticism